By Emily Alvarez

Stories of lived experience can be used to fight the stigma of mental illness and suicide and to help get people involved in the movement. These journeys humanize the suicide prevention movement and help other people seek help. This series on lived experience is a great chance to highlight a loss survivor’s story and the search for meaning after loss.

Jeff Leieritz recently became involved with the Carson J Spencer Foundation through his work with a construction trade association. His association, Associated Builders and Contractors, Inc. (ABC) recently joined the Construction Industry Alliance for Suicide Prevention. This move allowed him to come in contact with the Carson J Spencer Foundation. Jeff lost his father last year and has been trying to make meaning out of the loss ever since. This year, we want to focus on lived experience and share stories of finding meaning from loss and despair. This is his story:

I lost my dad to suicide on Valentine’s Day 2015. My dad was one of the most selfless people I’ve ever met; he was a teacher and middle school coach in San Bernardino, California and invested a lot of extra effort and time in his students and student athletes.

My dad was my coach growing up and was the best man in my wedding. I not only lost my dad, I lost one of my best friends. My wife had never seen me cry before my dad took his own life, but I do not think I can count the number of times she has seen it since.

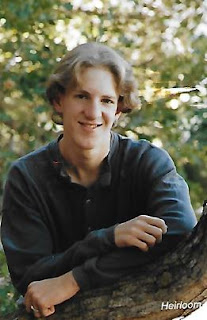

Jeff and his Dad

He and my mother made a lot of sacrifices to raise me in a way that has allowed me to be successful. It’s impossible to get through a day without seeing ways that my parents have touched my life. My work ethic and faith in Christ are deeply rooted in the way I was raised by both of my parents.

My dad was a father figure to so many people over the years, but never met my son, who shares his middle name with my dad. I never thought I would be in the position of raising my son without my dad around but I hope that I am able to instill in him the sense of compassion for other people that my dad lived every day.

Speaking at my dad’s memorial service was one of the most difficult things I have ever done. I remember watching him speak at his dad’s funeral a couple of years before and do not know how he made it through speaking without breaking down.

I didn’t make it past my first sentence without crying.

My mourning process is ongoing, there’s not a day that goes by that I do not miss my dad. The biggest challenge that I believe I have overcome in my mourning process is asking myself the what if questions.

What if I had recognized the signs?

What if I had known what this meant? I live on the East Coast now, what if I had been around more?

What if? What if? What if?

There’s no solace in pondering those questions and no healing. I believe that everything happens for a reason. I do not know that I will ever understand why my dad took his own life but I am also not going to heal if I keep asking myself these unanswerable questions.

Realizing that no good comes from these questions, whether I am asking them myself or feel like I need to answer them for others was a big moment in my mourning process.

I have attempted to maintain my dad’s legacy as a coach and leader in the community by establishing a memorial scholarship for student athletes from the Westside of San Bernardino who have excelled in the classroom and in athletics in his name. The first memorial scholarship was awarded a couple of months after he passed away. This past year we were able to raise enough money to award scholarships to two applicants.

Additionally, my employer, Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC), a national construction industry trade association representing nearly 21,000 members, has joined the Construction Industry Alliance for Suicide Prevention. As a part of the alliance ABC is taking an active role in raising awareness and distributing resources to companies about suicide prevention and mental health promotion.

I am proud of our involvement in the Construction Industry Alliance for Suicide Prevention and I find a purpose in trying to raise awareness and normalize conversations about mental health. I believe there is a crippling stigma that comes with discussing mental health issues and this stigma and hesitance only increases the feeling of isolation that people feel when they are battling suicidal thoughts. By normalizing conversations about mental health and suicide prevention, I believe that we can make people that are struggling feel less isolated.

I lost my dad at the age of 28, he never met my son, was not around to see me buy my first house, he’s already missed so much; I need to feel like I am using my experience in losing him and his life in a way that will have a positive impact on the world.

I think that my dad would be most proud of two things; his grandson and the scholarship we have created in his name.

The last conversation I had with my dad we talked about starting and I believe that my dad would be so proud to be a grandfather.

Jeff with his Dad at his wedding

My dad was really dedicated to the kids he coached and to the city of San Bernardino. Student athletes he coached dating back more than 20 years attended his service and I cannot think of a more meaningful or better way to honor his memory and commitment to the community.

I would tell people that recently lost someone to suicide that there is no healing, only frustration in going over the “what if” questions. For me it was also important to be patient in finding a meaning or purpose from my loss.

I look to take motivation from hardship; I needed a different approach to losing my dad. I do not like to feel sorry for myself but needed to let myself feel that way in losing my dad. It didn’t need to motivate me into action, it was awful and it was ok for it to just be awful.

The effects of a suicide loss are long-lasting and far-reaching. Many survivors look for ways to make meaning out of their loss and celebrate the life of their loved one. There are many wonderful organizations that provide life-saving suicide prevention programming. The Carson J Spencer Foundation elevates the conversation to make suicide prevention a health and safety priority. Through a variety of prevention programs, Carson J Spencer Foundation is changing the face of suicide loss. Whether you partner with our organization, or another, we encourage you to get involved. Giving a gift, in memory of a loved one lost, can help create the meaning that so many seek. For more information, please visit www.carsonjspencer.org.